Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA (1723 - 1792)

RA Collection: People and Organisations

The Royal Academy’s first president, Joshua Reynolds, was considered the leading portrait painter of his day and a key figure in the Academy. Still in print today, and widely translated, his groundbreaking Discourses in Art were hugely influential on the development of British art.

The son of a Devonshire reverend and schoolmaster, Reynolds received a comprehensive education before being apprenticed to the portrait painter Thomas Hudson aged 17. In 1749, he was invited to join the HMS Centurion on a voyage to the Mediterranean; Reynolds disembarked in Rome and stayed there for two years, studying the Old Masters. While in Rome he suffered from a bad cold which left him partially deaf so that he often carried an ear trumpet round with him, and was often depicted carrying the trumpet.

Soon after his return, Reynolds set up a studio in London and quickly established himself as a sought-after portrait painter, making important aristocratic connections in the process. His circle of friends included 18th-century notables such as the writer Dr Samuel Johnson, actor and playwright David Garrick and statesman Edmund Burke. He painted memorable portraits of all of them.

Despite remaining somewhat aloof from the politics that, even then, dogged London’s art-world, Reynolds was pre-eminent among England’s painters. His works were a key feature in London’s earliest exhibitions of contemporary art and he was the obvious choice to lead the artistic community as the President of the Royal Academy, upon its creation in 1768. However, Reynolds was not a court favourite and painted the King only once, in a commission for the opening of the Royal Academy’s first official home at Somerset House in 1780.

Between 1769 and 1790, Reynolds set out his theories on art in a series of fifteen lectures in the Royal Academy Schools, published as Discourses on Art. He argued that painters should look to classical and Renaissance art as their model and should seek to idealise nature rather than copy it, setting out what would become known as the “grand manner” of painting. Reynolds positioned paintings of epic, historic scenes as the highest genre of art, despite the fact that high demand for his portraits meant that he rarely painted them himself.

Reynolds used his knowledge of the Old Masters to invigorate many of his portraits. His full-length portrait of Captain Keppel depicting the naval commander energetically striding forward is actually based on the classical statue of the Apollo Belvedere. Some artists such as Nathanial Hone felt he was too reliant of Old Masters and painted a picture titled The Conjurer in which prints of Old Masters whirl around the conjurer which was a veiled reference to his practice. Another Royal Academician, Thomas Gainsborough, fell out with Reynolds for years before seeking reconciliation on his deathbed, writing that he had always “admired and sincerely loved Sir Joshua Reynolds”.

Reynolds’s death was greatly mourned. When he died in 1792, Edmund Burke’s eulogy honoured him as “the first Englishman who added the praise of the elegant arts to the other glories of his country”. His body lay in the Royal Academy before being moved to St. Paul’s Cathedral and the procession included ninety one carriages carrying many distinguished persons, and was followed by all the Academicians and students from the RA Schools. There is a statue by Alfred Drury, installed in 1931 and around this statue which still greets visitors to the Royal Academy today. The fountains and lights arranged around the statue reflect the alignment of planets, the moon and stars at midnight on the night of Reynolds’s birth.

RA Collections Decolonial Research Project - Extended Case Study

According to an account by the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, Reynolds stated his opposition to the slave-trade at a dinner with friends around 1787. Clarkson had shown the group samples of African cloth, and Reynolds ‘gave his unqualified approbation of the abolition of this cruel traffic’ (see Notes, 1). Reynolds also supported through subscription the second edition of the anti-slavery tract written by Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and sentiments on the evil of slavery (1791) (see Notes, 2). Cugoano had been a servant in the household of the artists Richard and Maria Cosway, and through the Cosways had met many prominent artists, writers and politicians.

Reynolds had a Black servant who appears to have joined his household around the mid-1760s. Unlike Cugoano, however, his name is not recorded despite the artist and writer James Northcote suggesting that the servant modelled for several of Reynolds’ paintings (see Notes, 3). Northcote stated that the man had been brought to Britain (presumably from the Caribbean) by the wife of Valentine Morris, a British landowner and politician who also owned plantations in Antigua and who was Governor of St Vincent from 1772-79. There are, however, inconsistencies and conflicting chronologies in this account (see Notes, 4).

Reynolds’ servant is described in Northcote’s Memoirs in connection with an incident in which he was the victim of a crime. According to this account, after accompanying an elderly lady who had dined with Reynolds to her home, he met some friends and found himself locked out on his return. He spent the night at a watch-house – an early form of a police station that also provided overnight accommodation for those unexpectedly with nowhere to sleep – where his watch was stolen by one of the ‘miserable company’ there. The thief was charged, with the servant as witness, and Northcote recalls that Reynolds learnt of this from reading an account of the Old Bailey proceedings in a newspaper. Hearing that the thief was to be condemned to death, Reynolds became angry with his servant and made him deliver his own food to the thief in prison, ‘as a penance’. Meanwhile, Reynolds successfully asked his friend Edmund Burke to have the thief’s sentence changed to transportation. Scholars have recently discovered that Reynolds’ servant was named John Shropshire, the thief was Thomas Windsor and that this incident took place in 1767 (Note 5). According to this account both Shropshire and the man who stole his watch were Black.

The same servant was said to be the model for the groom in the portrait of John Manners, Marquis of Granby (c.1766-70). This is one of a number of paintings by Reynolds which depict Black people, mostly as servants in portraits of wealthy white patrons, for example The Temple Family (1780-2), a portrait of Frederick William Ernest, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe, and a portrait of Lieutenant Paul Henry Ourry MP (c.1748). The Black model depicted as the groom in the latter painting has been identified as ‘Jersey’, but he was not Reynolds’ servant (see Notes, 6).

The following paragraph includes offensive language cited from an archival document. The original wording has been used to preserve its historical significance.

A Black servant also features in his portrait of Lady Keppel. see https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/portrait-of-lady-elizabeth-keppel. Details of eight appointments with Lady Keppel are recorded in Reynolds’ sitters’ book for 1761 (Reynolds used these books to log his sitters throughout his career – see Notes, 7). In December 1761, there are two separate appointments to capture the likeness of her female servant; Reynolds records these with the word ‘negro’ rather than recording her name. Such disregard for people of colour and their individuality was common in British society at this time.

Reynolds’ most famous depiction of a Black person is the portrait thought to show Francis Barber, the servant and heir of the lexicographer Samuel Johnson. The unfinished portrait, now in the Menil Collection, Houston, casts Barber as a romantic, almost heroic, figure against a stormy sky. The identity of the sitter is not completely certain, and it may even portray Reynolds’ own servant, but the careful treatment of the subject implies that Reynolds – or the person who commissioned the painting – held this sitter in high esteem. By the 1770s when this portrait was painted, Barber was likely assisting Johnson with revising his Dictionary of the English Language and it is possible that he commissioned the portrait of Barber, whom he held in great affection.

Interestingly, there are several versions of the original painting of Barber by Reynolds, copies by later artists and those in Reynolds’ immediate circle. It may be that Reynolds encouraged his students to copy and learn from this portrait. The original was also exhibited at the British Institution in 1813, when it would have been seen and possibly reproduced by many artists (see Notes, 8).

For more information on this research project, see this article https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/ra-collections-decolonial-research

Notes

Thomas Clarkson, History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (London, 1839), I:160-1; https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/TheHistoryoftheRiseProgressand_Acc/gKgNAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 (accessed 2 March 2022).

Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and sentiments on the evil or slavery; Or, the nature of servitude as admitted by the law of God, compared to the modern slavery of the Africans in the West-Indies; in an answer to the advocates for slavery and oppression. Addressed to the sons of Africa, by a native (London, 1791); James Northcote, Memoirs of Sir Joshua Reynolds (London, 1813), p. 117;https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0126566527/ECCO?u=lonlib&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=f994b30d&pg=1 (accessed March 2, 2022).

https://archive.org/details/memoirsofsirjosh00nortrich/page/116/mode/2up (accessed 2 March 2022).

James Northcote, Memoirs of Sir Joshua Reynolds (London, 1813), pp. 117-18; https://archive.org/details/memoirsofsirjosh00nortrich/page/116/mode/2up (accessed 2 March 2022). The chronology of events is difficult to determine due to inconsistencies in the biographies of Valentine Morris, his wife Mary Mordaunt and his daughter. Although according to Northcote, Reynolds’ Black servant was brought to England by Morris and entered Reynolds’ service after Morris’ death, this does not seem possible given that the anecdote described in his Memoirs is said to have taken place around 1768-9 but Morris died in 1789.

There is an account of the trial in the Old Bailey Online https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/17671021 (accessed January 2025) https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t17671021-44 (accessed January 2025). Jessie Park and Catherine Roach presented their research on this at the Paul Mellon Centre in 2024 https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/whats-on/forthcoming/naming-rights

Nicholas Penny (ed.), Reynolds (1986), p. 173.

Joshua Reynolds’ pocket book for 1761, RA Archive reference code REY/1/5; https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/archive/pocket-book-4?allfields=book&archivetitlefond=2.01.OG&date=&form=archives&index=6&name=&referencecode=&total_entries=29&utf8=%E2%9C%93 (accessed 7 March 2022).

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/reynolds-a-young-black-man-francis-barber-t01892 (accessed 7 March 2022).

Relevant ODNB entries

Postle, Martin. “Reynolds, Sir Joshua (1723–1792), portrait and history painter and art theorist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 2 Mar. 2022. https://www-oxforddnb-com.lonlib.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-23429.

Profile

Foundation Member

Born: 16 July 1723 in Plympton, Devon, England, United Kingdom

Died: 23 February 1792

Nationality: British

Elected RA: 10 December 1768

President from: 1768 - 1792

Gender: Male

Preferred media: Painting

Works by Sir Joshua Reynolds in the RA Collection

19 results

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Lavinia, Countess Spencer]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Lavinia, Countess Spencer

Mixed method engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Lavinia, Countess Spencer]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Lavinia, Countess Spencer

Mixed method engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Francis Hayman, R.A.]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Francis Hayman, R.A., 1756

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Theory]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Theory, 1779-1780

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Studio Experiments in Colour and Media]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Studio Experiments in Colour and Media

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Queen Charlotte]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Queen Charlotte, 1779

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Giuseppe Marchi]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Giuseppe Marchi, 1753

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of King George III]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of King George III, 1779

Oil on canvas

-

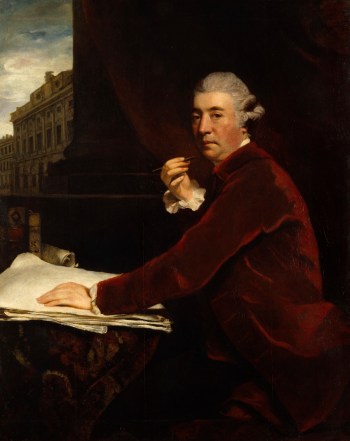

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Sir William Chambers, R.A.]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Sir William Chambers, R.A., ca. 1780

Oil on panel

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Self-portrait of Sir Joshua Reynolds, PRA]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Self-portrait of Sir Joshua Reynolds, PRA, ca. 1780

Oil on panel

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Spectacles belonging to Joshua Reynolds]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Spectacles belonging to Joshua Reynolds

Metal spectacles in a burgundy and brown leather case

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, O38647]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

O38647

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, O38646]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

O38646

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, O38645]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

O38645

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, O38643]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

O38643

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, O38640]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

O38640

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Keppel]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Keppel, 1762

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Annabella Bunbury (Lady Blake) as Juno]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Annabella Bunbury (Lady Blake) as Juno

Mezzotint

-

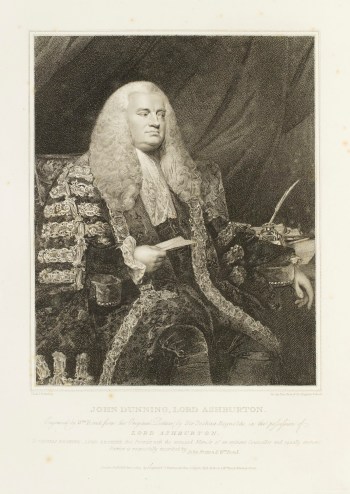

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of John Dunning, Lord Ashburton]()

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of John Dunning, Lord Ashburton, 4th June 1809

Stipple engraving

Works after Sir Joshua Reynolds in the RA Collection

32 results

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Garrick Between Tragedy and Comedy, after Sir Joshua Reynolds]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Garrick Between Tragedy and Comedy, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1 December 1811

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Sir Joshua Reynolds]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Sir Joshua Reynolds, 20 January 1811

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of John, Marquis of Granby]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of John, Marquis of Granby, 1 December 1810

Stipple engraving

-

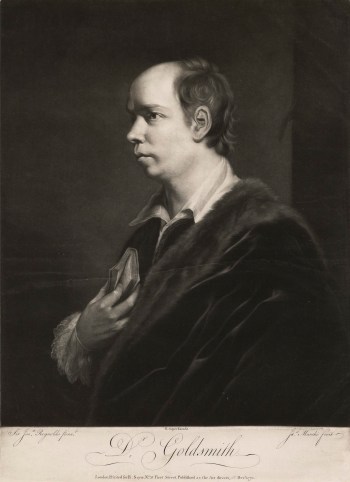

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Oliver Goldsmith]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Oliver Goldsmith, 1 December 1770

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Sir William Chambers RA]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Sir William Chambers RA, 1 March 1785

Stipple-engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Giuseppe Baretti]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Giuseppe Baretti, 6 March 1794

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of George III]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of George III, 18 June 1789

Stipple engraving

-

![William Blake, An Inquiry Into The Requisite Cultivation And Present State Of The Arts Of Design In England. By Prince Hoare.]()

William Blake

The Graphic Muse, 21 February 1806

Line engraving with stipple

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Samuel Johnson]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Samuel Johnson, 1 January 1787

Line engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Angelica Kauffman, R.A.]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Angelica Kauffman, R.A., 3 September 1780

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of James Boswell]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of James Boswell, c. 1825?

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Miss Theophila Palmer]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Miss Theophila Palmer, 14 July 1785

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Self portrait]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Self portrait, 1 March 1789

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Self-portrait]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Self-portrait, 1 February 1795

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Self-portrait]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Self-portrait, 10 July 1770

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, James Paine, Architect and James Paine Jun.]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

James Paine, Architect and James Paine Jun., [1767]

Mezzotint

-

![Francis Haward ARA, Mrs. Siddons in the character of the Tragic Muse]()

Francis Haward ARA

Mrs. Siddons in the character of the Tragic Muse, 4 June 1787

Stipple-engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Sir Jeffery Amherst]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Sir Jeffery Amherst, [1766?]

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Self-portrait]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Self-portrait, 1 December 1780

Mezzotint

-

![James Ward RA, Mrs. Billington as St. Cecilia]()

James Ward RA

Mrs. Billington as St. Cecilia, 10 January 1803

Mezzotint

-

![Francis Haward ARA, George, Prince of Wales]()

Francis Haward ARA

George, Prince of Wales, 18 January 1793

Stipple-engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, The Holy Family]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

The Holy Family, 12 August 1792

Line-engraving

-

![William Say, Cupid and Psyche]()

William Say

Cupid and Psyche, 1814

Mezzotint

-

![William Say, The Society of Dilettanti]()

William Say

The Society of Dilettanti, [April 1821]

Mezzotint

-

![Charles Turner ARA, The Society of Dilettanti]()

Charles Turner ARA

The Society of Dilettanti, [April 1821]

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Sir William Chambers, K.P.S., Treasurer of the Royal Academy]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Sir William Chambers, K.P.S., Treasurer of the Royal Academy, 1 December 1780

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Samuel Johnson]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Samuel Johnson, 1770

Mezzotint

-

![Joseph Grozer, The Death of Dido]()

Joseph Grozer

The Death of Dido, 30 May 1796

Mezzotint

-

![Henry Thomson RA, The Infant Hercules]()

After Henry Thomson RA

The Infant Hercules, ?1790s

Oil on canvas

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Edmund Burke]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Edmund Burke, 3 October 1771

Mezzotint

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of George Colman the elder]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of George Colman the elder, 8 March 1813

Stipple engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Portrait of Giuseppe Baretti]()

After Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Portrait of Giuseppe Baretti, 6 March 1794

Stipple engraving

Works associated with Sir Joshua Reynolds in the RA Collection

182 results

-

![François Vivares, Jupiter and Europa]()

François Vivares

Jupiter and Europa, 10 April 1771

Line engraving

-

![Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Lady with a Fan]()

Attributed to Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Lady with a Fan, ca. 1746

Oil on panel

-

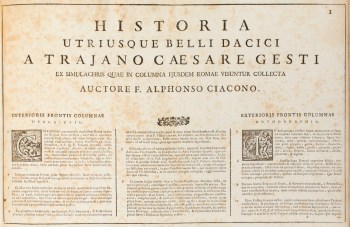

![Giacomo De' Rossi, Letterpressed title-page of the latin descriptions of the plates]()

Giacomo De' Rossi

Letterpressed title-page of the latin descriptions of the plates, 1672

-

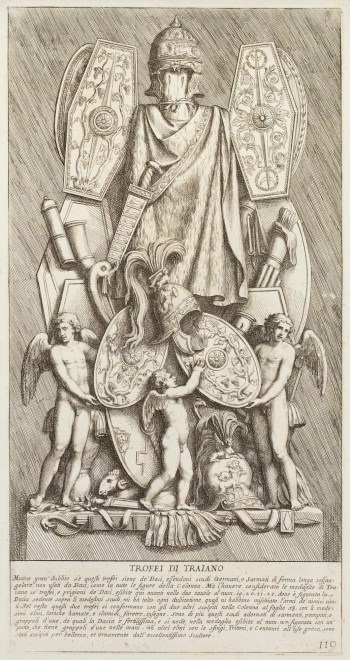

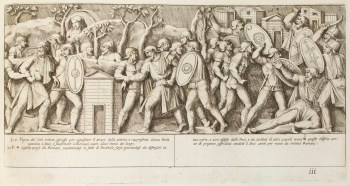

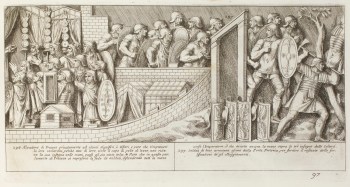

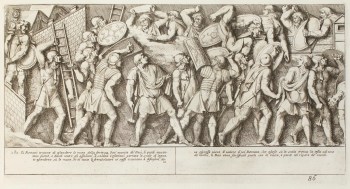

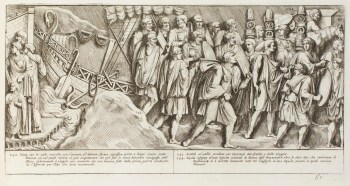

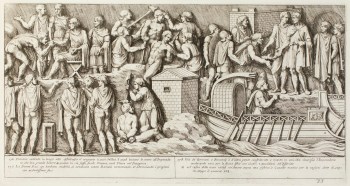

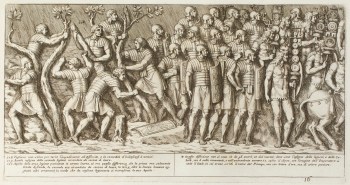

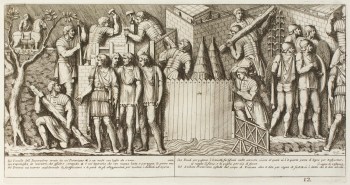

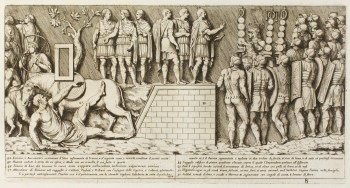

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 119: Other war trophies of the Emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 119: Other war trophies of the Emperor Trajan, 1672

-

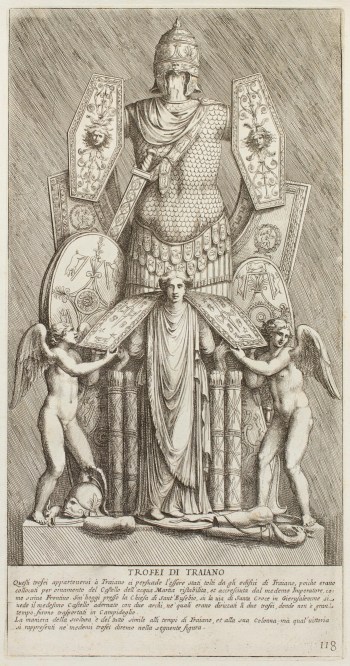

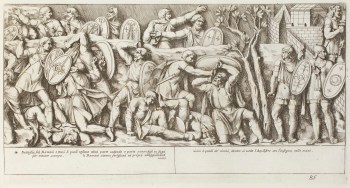

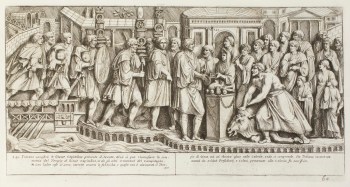

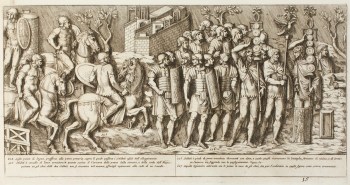

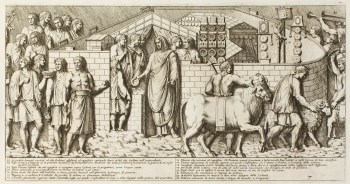

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 118: War trophies of the Emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 118: War trophies of the Emperor Trajan, 1672

-

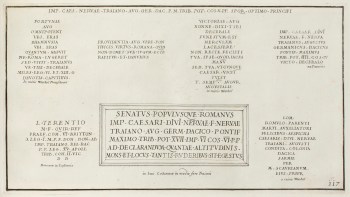

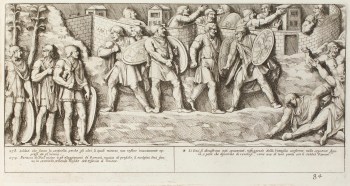

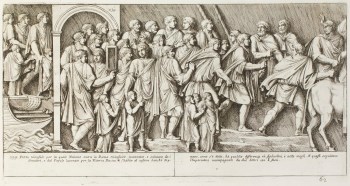

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 117: Latin inscriptions celebrating the victory over the Dacians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 117: Latin inscriptions celebrating the victory over the Dacians, 1672

-

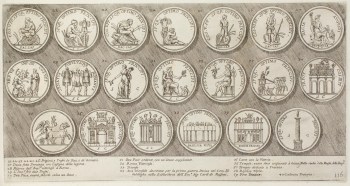

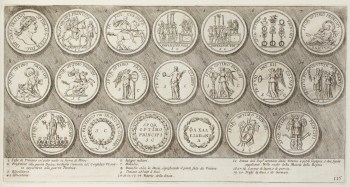

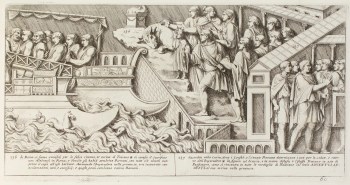

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 116: other series of coins celebrating the victory over the Dacians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 116: other series of coins celebrating the victory over the Dacians, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 115: Coins celebrating the victory over the Dacians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 115: Coins celebrating the victory over the Dacians, 1672

-

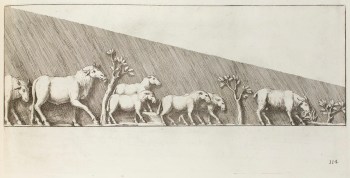

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 114: Dacian cattle]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 114: Dacian cattle , 1672

-

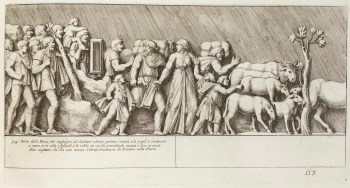

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 113: Dacian families migrating to another territories]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 113: Dacian families migrating to another territories, 1672

-

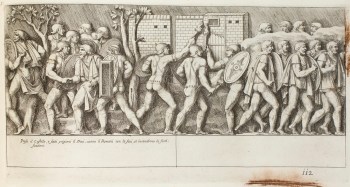

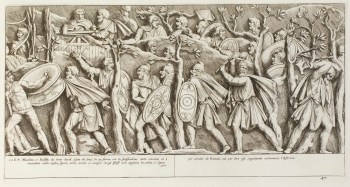

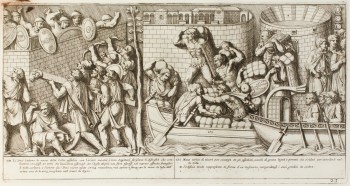

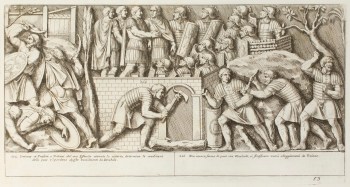

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 112: Roman soldiers setting fire to the Dacian fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 112: Roman soldiers setting fire to the Dacian fortifications , 1672

-

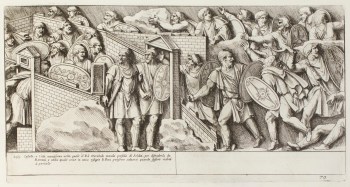

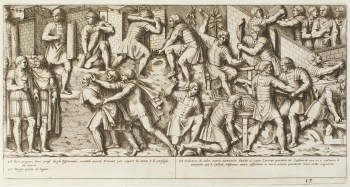

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 111: Roman soldiers imprisoning some Dacian soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 111: Roman soldiers imprisoning some Dacian soldiers, 1672

-

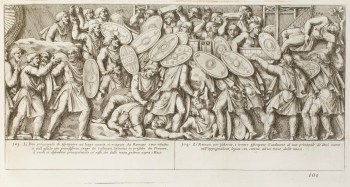

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 110: Roman soldiers making Dacian prisoners]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 110: Roman soldiers making Dacian prisoners , 1672

-

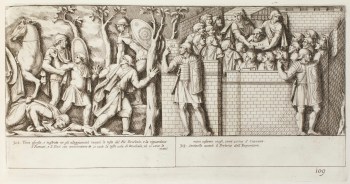

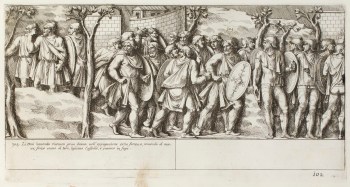

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 109: Roman soldiers capturing the Dacian officials]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 109: Roman soldiers capturing the Dacian officials, 1672

-

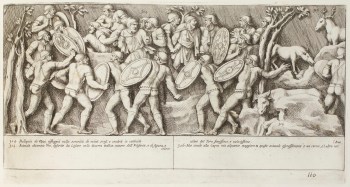

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 108: Roman soldiers capturing the Dacian officials]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 108: Roman soldiers capturing the Dacian officials, 1672

-

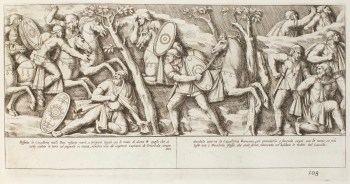

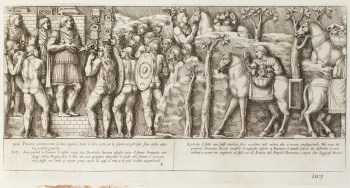

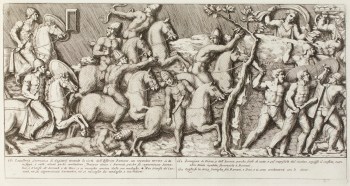

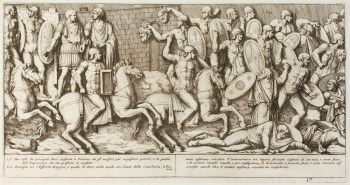

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 107: the Dacian cavalry fleeing the Romans]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 107: the Dacian cavalry fleeing the Romans, 1672

-

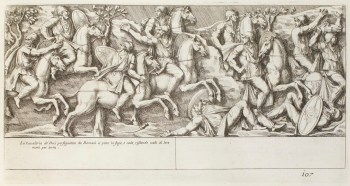

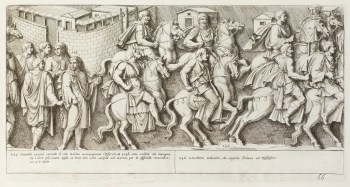

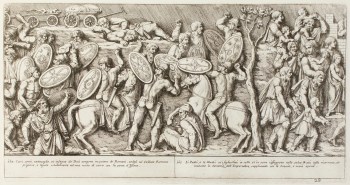

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 106: Roman cavalry chasing the Decian cavalry]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 106: Roman cavalry chasing the Decian cavalry, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 105: a group of Dacians surrendering to Trajan and bringign gifts]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 105: a group of Dacians surrendering to Trajan and bringign gifts, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 104: Decebalus addressing the Dacians; and Decebalus stabbing himself to death]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 104: Decebalus addressing the Dacians; and Decebalus stabbing himself to death, 1672

-

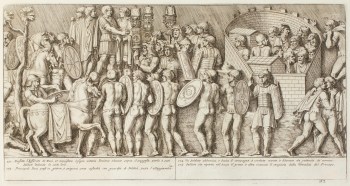

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 103: Emperor Trajan standing addressing two Roman legions while some soldiers carry Decebalus'treasures]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 103: Emperor Trajan standing addressing two Roman legions while some soldiers carry Decebalus'treasures , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 102: Dacians fleeing after being defeated]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 102: Dacians fleeing after being defeated , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 101: Dacians assaulting a Roman fortress]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 101: Dacians assaulting a Roman fortress, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 100: Dacians leaving their fortifications in order to attack the Romans]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 100: Dacians leaving their fortifications in order to attack the Romans , 1672

-

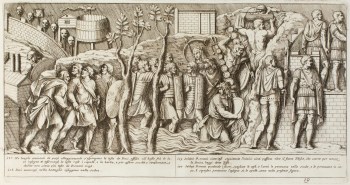

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 99: Dacian ambassadors kneeling before Emperor Trajan asking for peace]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 99: Dacian ambassadors kneeling before Emperor Trajan asking for peace, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 97: Roman soldiers listening to Emperor Trajan's speech]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 97: Roman soldiers listening to Emperor Trajan's speech , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 96: Roman soldier distributing wheat to other soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 96: Roman soldier distributing wheat to other soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 95: a group of Dacians at right kneeling and asking for Trajan's clemence]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 95: a group of Dacians at right kneeling and asking for Trajan's clemence , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 94: Dacians running out of the city and askign for clemence]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 94: Dacians running out of the city and askign for clemence , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 93: Dacians poisoning themself after their defeat]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 93: Dacians poisoning themself after their defeat, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 92: Dacians setting fire to one of their city]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 92: Dacians setting fire to one of their city, 1672

-

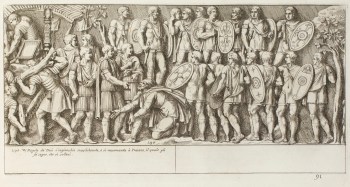

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 91: a Dacian kneeling before emperor Trajan at centre]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 91: a Dacian kneeling before emperor Trajan at centre, 1672

-

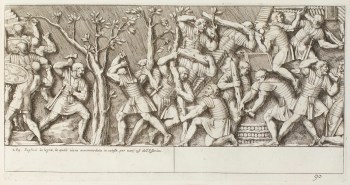

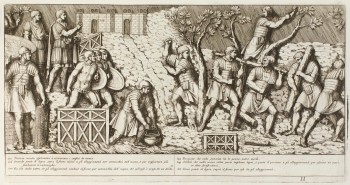

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 90: Roman soldiers cutting trees and making piles of wood]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 90: Roman soldiers cutting trees and making piles of wood, 1672

-

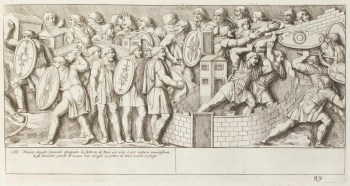

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 89: Roman soldiers destroying a Dacian fortress]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 89: Roman soldiers destroying a Dacian fortress, 1672

-

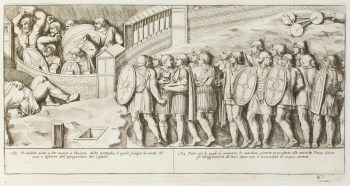

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 88: Dacian soldiers stop the pace of Trajan's troops coming to the rescue]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 88: Dacian soldiers stop the pace of Trajan's troops coming to the rescue, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 87: a Roman soldier informing Emperor Trajan about the battle with the Dacians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 87: a Roman soldier informing Emperor Trajan about the battle with the Dacians, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 86: Roman soldiers attempting to climb the Dacian defense wall]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 86: Roman soldiers attempting to climb the Dacian defense wall, 1672

-

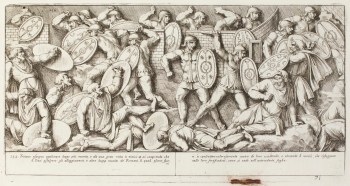

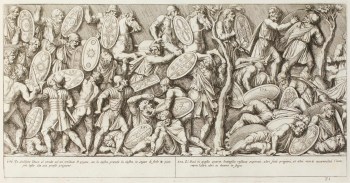

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 85: Battle between Roman and Dacian soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 85: Battle between Roman and Dacian soldiers , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 84: Dacians presiding their camps]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 84: Dacians presiding their camps, 1672

-

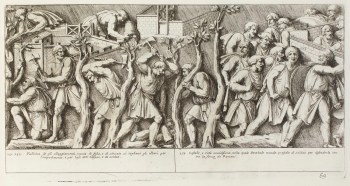

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 83: Troops harvesting the crops]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 83: Troops harvesting the crops, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 82: Continued march of the armies]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 82: Continued march of the armies, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 81: Veteran soldiers and Romans with musical instruments]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 81: Veteran soldiers and Romans with musical instruments , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 80: Emperor Trajan sending his soldiers to battler]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 80: Emperor Trajan sending his soldiers to battler, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 79: Emperor trajan addressing the Roman soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 79: Emperor trajan addressing the Roman soldiers, 1672

-

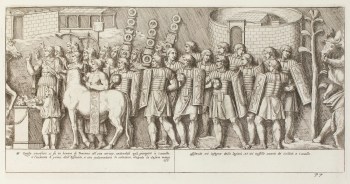

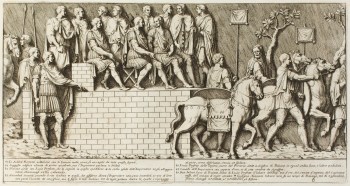

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 78: two men bringing the bull, the ram and the pork for the sacrifice]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 78: two men bringing the bull, the ram and the pork for the sacrifice , 1672

-

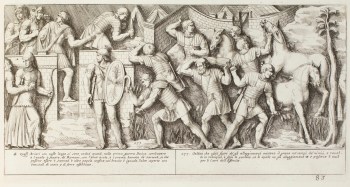

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 77: a sacrifice in honour of emperor Trajan's arrival]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 77: a sacrifice in honour of emperor Trajan's arrival, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 76: Emperor Trajan and Hadrian leading the Roman army]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 76: Emperor Trajan and Hadrian leading the Roman army , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 75: Dacian and Sarmatian soldiers sent to Emperor Trajan in order to establish the condition for the peace]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 75: Dacian and Sarmatian soldiers sent to Emperor Trajan in order to establish the condition for the peace, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 74: Emperor Trajan followed by veterans; and Trajan performing a sacrifice]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 74: Emperor Trajan followed by veterans; and Trajan performing a sacrifice, 1672

-

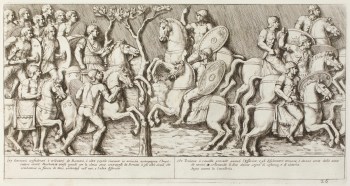

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 73: Emperor Trajan on horseback leading the Roman cavalry]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 73: Emperor Trajan on horseback leading the Roman cavalry, 1672

-

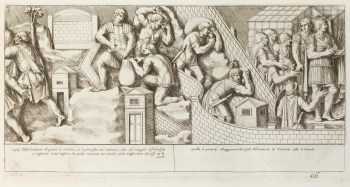

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 72: Roman soldiers occupying Dacian fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 72: Roman soldiers occupying Dacian fortifications, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 71: Dacian soldiers attaching a Roman camp]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 71: Dacian soldiers attaching a Roman camp, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 70: Dacian soldiers guarding a city]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 70: Dacian soldiers guarding a city, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 69: a group of men cutting trees and consolidating buildings]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 69: a group of men cutting trees and consolidating buildings, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 68: Romans and Dacians assist to a sacrifice performed by the Emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 68: Romans and Dacians assist to a sacrifice performed by the Emperor Trajan, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 67: Iazyges greeting Emperor Trajan; and Trajan performing a sacrifice]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 67: Iazyges greeting Emperor Trajan; and Trajan performing a sacrifice, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 66: Roman sacerdotes following a Roman cavalry]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 66: Roman sacerdotes following a Roman cavalry , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 65: Emperor Trajan land on the shore and advabce by land]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 65: Emperor Trajan land on the shore and advabce by land, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 64: Emperor Trajan making a sacrifice to Jupiter]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 64: Emperor Trajan making a sacrifice to Jupiter, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 63: a group of Roman soldiers greeting emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 63: a group of Roman soldiers greeting emperor Trajan, 1672

-

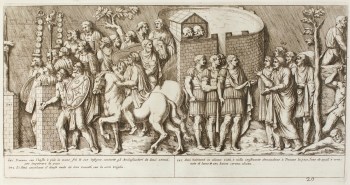

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 62: emperor Trajan entering a Roman town through a triumphal arch]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 62: emperor Trajan entering a Roman town through a triumphal arch

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 61: a group of Romans greeting the Emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 61: a group of Romans greeting the Emperor Trajan, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 60: Romans making sacrifice in honour of emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 60: Romans making sacrifice in honour of emperor Trajan, 1672

-

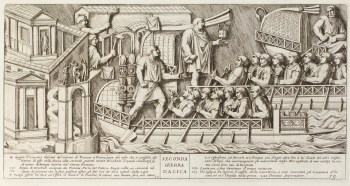

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 59: Emperor Trajan leaving for the Second Dacian War]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 59: Emperor Trajan leaving for the Second Dacian War, 1672

-

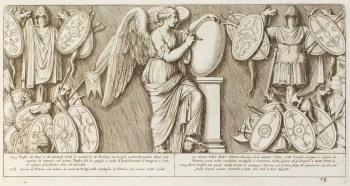

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 58: the personification of Victory writing on a shield]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 58: the personification of Victory writing on a shield , 1672

-

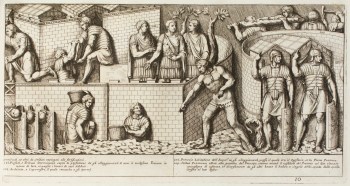

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 57: Emperor Trajan and Decebalus addressing the Thirteenth Legion]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 57: Emperor Trajan and Decebalus addressing the Thirteenth Legion, 1672

-

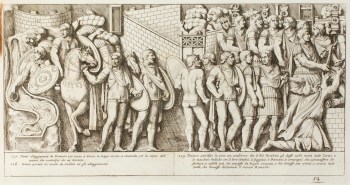

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 56: Dacian officials kneeling before Emperor Trajan while castles and fortifications are demolished]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 56: Dacian officials kneeling before Emperor Trajan while castles and fortifications are demolished, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 55: Decebalus and the Dacians kneeling before Emperor Trajan askign for clemence]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 55: Decebalus and the Dacians kneeling before Emperor Trajan askign for clemence, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 54: Emperor Trajan establishing peace with the Decebalus]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 54: Emperor Trajan establishing peace with the Decebalus, 1672

-

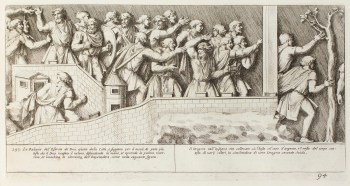

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 52: Last battle between Dacians and Romans]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 52: Last battle between Dacians and Romans , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 51: Roman soldiers bringing two heads of Dacian prisoners before emperor Trajan]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 51: Roman soldiers bringing two heads of Dacian prisoners before emperor Trajan, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 50: Dacians being defeated by the Romans soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 50: Dacians being defeated by the Romans soldiers , 1672

-

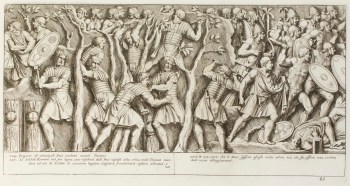

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 49: Dacians ambushing Roman soldiers while cutting trees in the forests]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 49: Dacians ambushing Roman soldiers while cutting trees in the forests, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 48: Roman soldiers cutting trees and building new camps]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 48: Roman soldiers cutting trees and building new camps, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 47: Dacians fighting the Roman and Sarmatian soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 47: Dacians fighting the Roman and Sarmatian soldiers , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 46: Roman and Sarmatian soldiers fighting the Dacians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 46: Roman and Sarmatian soldiers fighting the Dacians , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 45: Emperor Trajan receiving two Dacians while Roman soldiers build new fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 45: Emperor Trajan receiving two Dacians while Roman soldiers build new fortifications, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 44: The defeated Dacians seek shelter in the forests]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 44: The defeated Dacians seek shelter in the forests, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 42: Praetorian guards]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 42: Praetorian guards, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 40: emperor Trajan on horseback, and Roman soldiers building camps]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 40: emperor Trajan on horseback, and Roman soldiers building camps, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 38: Emperor Trajan addressing the soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 38: Emperor Trajan addressing the soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 37: Emperor Trajan sacrificing a pork, a ram, and a bull]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 37: Emperor Trajan sacrificing a pork, a ram, and a bull, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 36: Emperor Trajan receiving the Dacian ambassadors, Roman soldiers building fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 36: Emperor Trajan receiving the Dacian ambassadors, Roman soldiers building fortifications, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 35: Emperor Trajan discussing with soldiers a plan to fight the enemies]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 35: Emperor Trajan discussing with soldiers a plan to fight the enemies, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 34: Emperor Trajan leading the army ouside the camp to fight]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 34: Emperor Trajan leading the army ouside the camp to fight , 1672

-

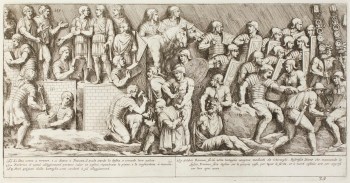

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 33: Emperor Trajan distributing the congiary; Dacian women torturing Roman prisoners with torches, allies of the Romans bringing provisions]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 33: Emperor Trajan distributing the congiary; Dacian women torturing Roman prisoners with torches, allies of the Romans bringing provisions, 1672

-

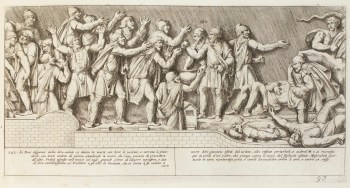

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 32: Dacian soldiers being defeated by the Roman soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 32: Dacian soldiers being defeated by the Roman soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 31: Dacian soldiers being defeated by the Roman soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 31: Dacian soldiers being defeated by the Roman soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 30: Roman soldiers preparing for the fourth battle with the Dacians / engraved plate from Colonna Traiana by Pietro Santi Bartoli, published by Giacomo de Rossi (Rome, 1672)]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 30: Roman soldiers preparing for the fourth battle with the Dacians / engraved plate from Colonna Traiana by Pietro Santi Bartoli, published by Giacomo de Rossi (Rome, 1672), 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 29: Dacian soldiers being received by Trajan, Roman soldiers are consolidating walls, doctors are giving assistance]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 29: Dacian soldiers being received by Trajan, Roman soldiers are consolidating walls, doctors are giving assistance , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 28: Battle between Romna soldiers and Decians]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 28: Battle between Romna soldiers and Decians, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 27: Sarmatian cavalry fleeing the Roman army]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 27: Sarmatian cavalry fleeing the Roman army, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 26: Emperor Trajan on horseback leading his army against Decebal]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 26: Emperor Trajan on horseback leading his army against Decebal, 1672

-

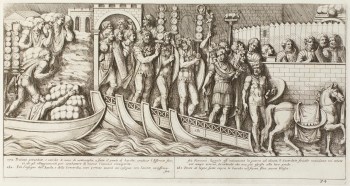

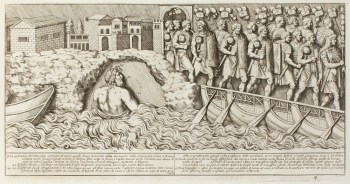

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 25: The emperor Trajan's landing]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 25: The emperor Trajan's landing, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 24: emperor Trajan entering the city in a boat]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 24: emperor Trajan entering the city in a boat , 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 23: Dacians besieging Roman a fortress and Romans bringing provisions]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 23: Dacians besieging Roman a fortress and Romans bringing provisions, 1672

-

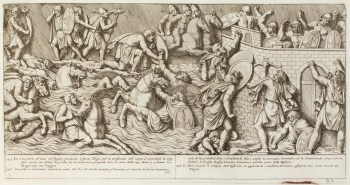

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 22: Dacians being caught in a swollen river, the Sarmatian cavalry attacking a Roman fortress]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 22: Dacians being caught in a swollen river, the Sarmatian cavalry attacking a Roman fortress, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 21: Dacians defeted, Emperor Trajan ordering his soldiers to free the women and the children]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 21: Dacians defeted, Emperor Trajan ordering his soldiers to free the women and the children, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 19: battle scene with Dacians Dacians fleeing and the Romans and victorious Roman soldiers crossing Tisa river with trophies]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 19: battle scene with Dacians Dacians fleeing and the Romans and victorious Roman soldiers crossing Tisa river with trophies, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 18: Dacian and Roman soldiers asking for Jupiter's protection, a group of men at centre carrying the dead body of a Dacian prisoner]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 18: Dacian and Roman soldiers asking for Jupiter's protection, a group of men at centre carrying the dead body of a Dacian prisoner, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 17: Roman soldiers at right presenting two heads of Dacian prisoners before emperor Trajans]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 17: Roman soldiers at right presenting two heads of Dacian prisoners before emperor Trajans, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 16: Roman soldiers cutting trees and another group wearing armour and carrying war trophies]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 16: Roman soldiers cutting trees and another group wearing armour and carrying war trophies, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 15: A group of Roman soldiers on horseback crossing a wooden bridge, and Roman soldiers in armour]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 15: A group of Roman soldiers on horseback crossing a wooden bridge, and Roman soldiers in armour, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 53: Emperor Trajan determining the conditions for a peace treatise with the Decebalus]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 53: Emperor Trajan determining the conditions for a peace treatise with the Decebalus, 1672

-

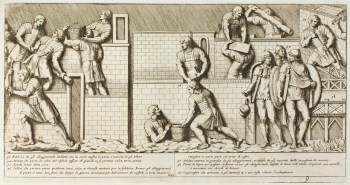

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 14: Roman soldiers building fortifications, soldiers holding the horses of the emperor, and soldiers guarding the Porta Pretoria]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 14: Roman soldiers building fortifications, soldiers holding the horses of the emperor, and soldiers guarding the Porta Pretoria, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 13: two Dacian prisoners being presented before Emperor Trajan while other soldiers building fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 13: two Dacian prisoners being presented before Emperor Trajan while other soldiers building fortifications, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 12: Emperor Trajan observing the fortifications built by the Roman soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 12: Emperor Trajan observing the fortifications built by the Roman soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 11: Emperor Trajan sending explorers and soldiers cutting trees]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 11: Emperor Trajan sending explorers and soldiers cutting trees, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 10: Emperor Trajan supervises the works at the camp with a Prefect and a Tribun]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 10: Emperor Trajan supervises the works at the camp with a Prefect and a Tribun, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 9: soldiers building a camp]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 9: soldiers building a camp, 1672

-

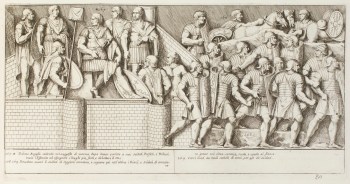

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 8: Emperor Trajan addressing the soldiers]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 8: Emperor Trajan addressing the soldiers, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 7: Emperor Trajan making a sacrifice]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 7: Emperor Trajan making a sacrifice, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 6: Emperor Trajan sitting on a camp stool discussing with Lucio Prefetto]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 6: Emperor Trajan sitting on a camp stool discussing with Lucio Prefetto , 1672

-

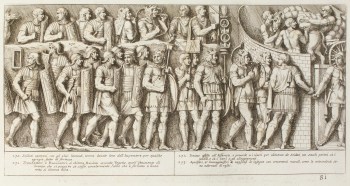

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 5: Roman soldiers marching carrying war trophies, led by soldiers on horseback]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 5: Roman soldiers marching carrying war trophies, led by soldiers on horseback, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 4: the statue of river Danube and the army crossing the river on a bridge made of boats]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 4: the statue of river Danube and the army crossing the river on a bridge made of boats, 1672

-

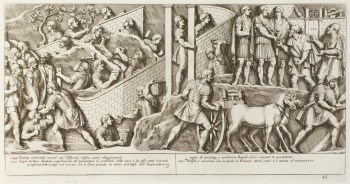

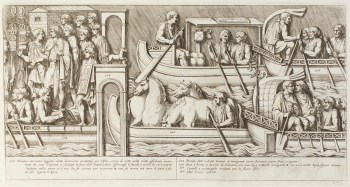

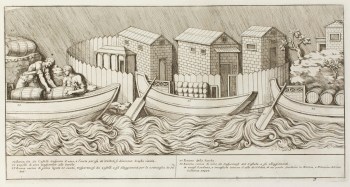

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 3: 'Scapha vinaria', boats for transporting wine, oil and grain to the fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 3: 'Scapha vinaria', boats for transporting wine, oil and grain to the fortifications, 1672

-

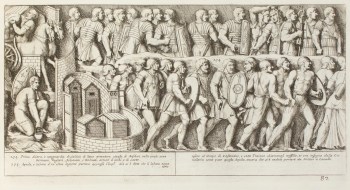

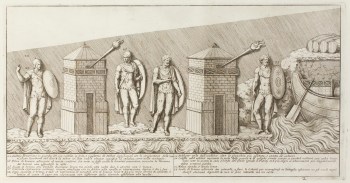

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 2: Praetorian soldiers and fortifications]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 2: Praetorian soldiers and fortifications, 1672

-

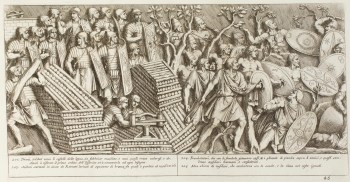

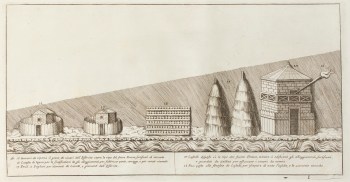

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 1: granary, heap of wood for fortifications, bundles of horse feed, castles]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 1: granary, heap of wood for fortifications, bundles of horse feed, castles , 1672

-

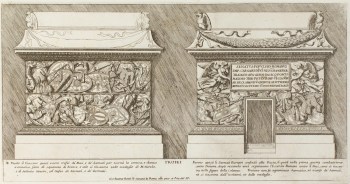

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Right and left sides of the column plinth showing the 'Throphies']()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Right and left sides of the column plinth showing the 'Throphies', 1672

-

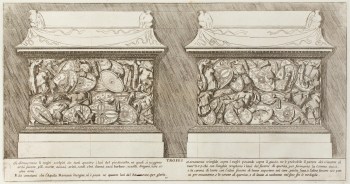

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Front and back sides of the column plinth showing the 'Throphies']()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Front and back sides of the column plinth showing the 'Throphies', 1672

-

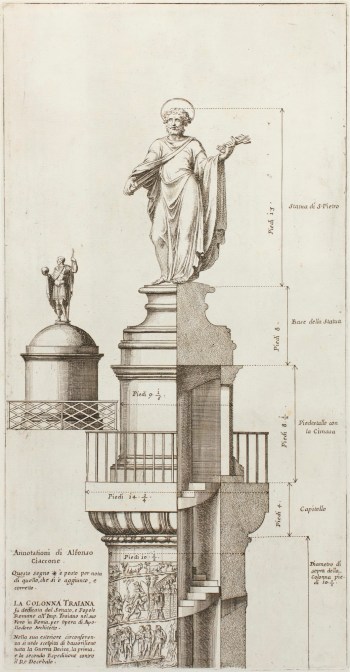

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Elevation and interior section of the top of the column]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Elevation and interior section of the top of the column, 1672

-

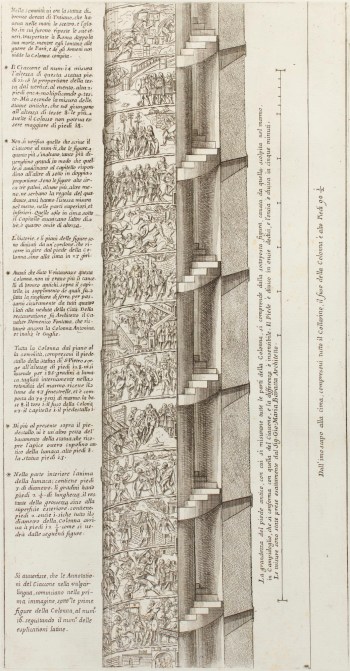

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Elevation and interior section of the body of the column]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Elevation and interior section of the body of the column, 1672

-

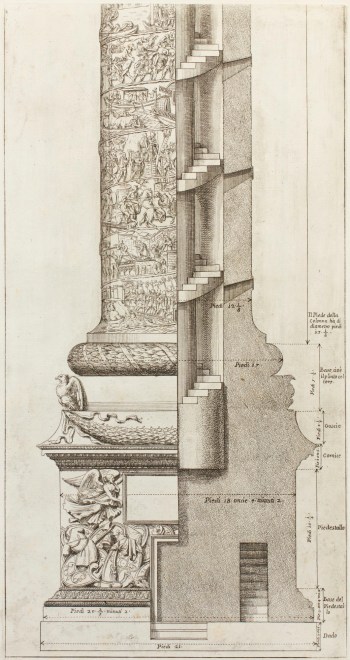

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Elevation and interior section of the base of the column]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Elevation and interior section of the base of the column, 1672

-

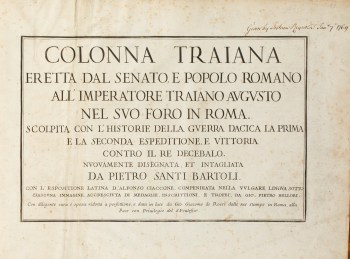

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Colonna Traiana]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Colonna Traiana, 1672

-

![Pietro Santi Bartoli, Plate 20: Emperor Trajan receiving the Dacian envoy]()

Pietro Santi Bartoli

Plate 20: Emperor Trajan receiving the Dacian envoy, 1672

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Stamp of Jacopo Giunti (from Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite De' Piu Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, E Architettori)]()

Giorgio Vasari

Stamp of Jacopo Giunti (from Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite De' Piu Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, E Architettori), 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Perino del Vaga]()

Giorgio Vasari

Perino del Vaga, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Sebastiano Veneziano]()

Giorgio Vasari

Sebastiano Veneziano, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Giulio Romano]()

Giorgio Vasari

Giulio Romano, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Antonio da Sangallo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Antonio da Sangallo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Marcantonio Raimondi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Marcantonio Raimondi, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Valerio Vicentino]()

Giorgio Vasari

Valerio Vicentino, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Baccio D'Agnolo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Baccio D'Agnolo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Granacci]()

Giorgio Vasari

Francesco Granacci, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Liberale da Verona]()

Giorgio Vasari

Liberale da Verona, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Palma il Giovane]()

Giorgio Vasari

Palma il Giovane, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Parmigianino]()

Giorgio Vasari

Parmigianino, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Border for a portrait of Marco Calabrese]()

Giorgio Vasari

Border for a portrait of Marco Calabrese, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Morto da Feltre]()

Giorgio Vasari

Morto da Feltre, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Franciabigio]()

Giorgio Vasari

Franciabigio, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Bartolomeo Ramenghi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Bartolomeo Ramenghi, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Rosso Fiorentino]()

Giorgio Vasari

Rosso Fiorentino, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Polidoro da Caravaggio]()

Giorgio Vasari

Polidoro da Caravaggio, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Girolamo da Treviso]()

Giorgio Vasari

Girolamo da Treviso, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Giovanni Antonio Sogliani]()

Giorgio Vasari

Giovanni Antonio Sogliani, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Il Pordenone]()

Giorgio Vasari

Il Pordenone, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Alfonso Lombardi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Alfonso Lombardi , 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Properzia de' Rossi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Properzia de' Rossi, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Giovan Francesco Penni]()

Giorgio Vasari

Giovan Francesco Penni, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Baldassarre Peruzzi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Baldassarre Peruzzi, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Lorenzo Lotti]()

Giorgio Vasari

Lorenzo Lotti, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Lorenzo di Credi]()

Giorgio Vasari

Lorenzo di Credi, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Baccio da Montelupo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Baccio da Montelupo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Benedetto da Rovezzano]()

Giorgio Vasari

Benedetto da Rovezzano, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Andrea dal Monte Sansovino]()

Giorgio Vasari

Andrea dal Monte Sansovino, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Vincenzo Tamagni]()

Giorgio Vasari

Vincenzo Tamagni , 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Andrea Ferrucci]()

Giorgio Vasari

Andrea Ferrucci, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Domenico Puligo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Domenico Puligo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Simone del Pollaiolo ( Il Cronaca)]()

Giorgio Vasari

Simone del Pollaiolo ( Il Cronaca), 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Guillaume de Marcillat]()

Giorgio Vasari

Guillaume de Marcillat, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio)]()

Giorgio Vasari

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Giuliano da Sangallo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Giuliano da Sangallo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Decorative frame for portrait of Pietro Torrigiano]()

Giorgio Vasari

Decorative frame for portrait of Pietro Torrigiano , 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Raffaellino del Garbo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Raffaellino del Garbo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Andrea del Sarto]()

Giorgio Vasari

Andrea del Sarto, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Mariotto Albertinelli]()

Giorgio Vasari

Mariotto Albertinelli, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Fra Bartolomeo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Fra Bartolomeo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Donato Bramante]()

Giorgio Vasari

Donato Bramante, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Piero di Cosimo]()

Giorgio Vasari

Piero di Cosimo, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Decorative frame for portrait of Correggio]()

Giorgio Vasari

Decorative frame for portrait of Correggio, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Giorgione]()

Giorgio Vasari

Giorgione, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo da Vinci]()

Giorgio Vasari

Leonardo da Vinci, 1791 [-1795]

Woodcut on laid paper

-

![Unidentified photographer, A group of 110 photographs of sculpture by Francis Derwent Wood R.A.]()

Unidentified photographer

A group of 110 photographs of sculpture by Francis Derwent Wood R.A.

-

![Giuseppe Ceracchi, Bust of Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A.]()

Giuseppe Ceracchi

Bust of Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A., ca. 1778

Marble

-

![Unknown, Cast of a bust of Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A.]()

Unknown

Cast of a bust of Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A., ca. 1778

Plaster cast

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Madonna and Child from the Cupola of the church of St. John at Parma attributed to Correggio]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Madonna and Child from the Cupola of the church of St. John at Parma attributed to Correggio, 1789

Etching and aquatint

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Madonna and Child attributed to Correggio]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Madonna and Child attributed to Correggio, 1789

Crayon-manner etching

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Study of a nude bearded man seen half-length attributed to Carlo Cignani]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Study of a nude bearded man seen half-length attributed to Carlo Cignani , 1789

Crayon-manner etching

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Study of Icarus (?) attributed to Rubens]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Study of Icarus (?) attributed to Rubens, 1789

Crayon-manner etching

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Parmigianino's 'Madonna of St Margaret']()

Conrad Martin Metz

Parmigianino's 'Madonna of St Margaret' , 1789

Etching

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist /]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist /, 1789

Etching and aquatint printed in colour

-

![Conrad Martin Metz, Studies of man (front and back), harm, and head of a horse]()

Conrad Martin Metz

Studies of man (front and back), harm, and head of a horse , 1789

Etching and aquatint printed in colour

-

![, Ivory miniature of Joshua Reynolds]()

Ivory miniature of Joshua Reynolds

Watercolour on ivory

Associated books

76 results

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

A discourse, delivered to the students of the Royal Academy, on the distribution of the prizes, December 11, 1769, by the President [Sir Joshua Reynolds] - London: 1769

14/3025

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

The Discourses Of Sir Joshua Reynolds; Illustrated By Explanatory Notes & Plates By John Burnet, F.R.S. - London.: 1842.

07/1662

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

The Literary Works Of Sir Joshua Reynolds, First President Of The Royal Academy. To Which Is Prefixed, A Memoir Of The Author; With Remarks On His Professional Character, Illustrative Of His Principles And Practice. By Henry William Beechey. In Two Volumes. Vol. I. (II.) - London:: 1835.

05/5039

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA

Sir Joshua Reynolds' Notes And Observations On Pictures, Chiefly Of The Venetian School, Being Extracts From His Italian Sketch Books; Also, The Rev. W. Mason's Observations On Sir Joshua's Method Of Coloring. And Some Unpublished Letters Of Dr. Johnson, Malone, And Others. With An Appendix, Containing A Transcript Of Sir Joshua's Account Book, Showing What Pictures He Painted And The Prices Paid For Them. Edited By William Cotton, Esq. - London:: [1859]

05/4008