Michael Craig-Martin: living colour

By Ravi Ghosh

Published on 28 August 2024

Michael Craig-Martin RA speaks to Ravi Ghosh about why objects became his obsession, ahead of his colourful retrospective in our Main Galleries.

From the Autumn 2024 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Michael Craig-Martin RA thinks London is still the greatest city on earth. This feels slightly unfashionable in today’s economic and social climate, but his reasons are intimately connected to his career – and to his upcoming Royal Academy show. When the Dublin-born artist first came to England in 1966 to teach at Bath Academy of Art, he didn’t know a single person in the UK. He had just spent five years at the Yale School of Art, immersed in Pop art, Minimalism, Conceptual art and upheavals in music, design and architecture. At that time, the London art world was embryonic, despite the exceptional quality of its artists and a strong art school tradition. “I think of myself as having been a very privileged immigrant,” he tells me in his Islington studio. “Would this have happened to me if I had gone to Paris and not to London? I don’t think so.”

‘This’ is his major retrospective exhibition at the RA, a focal point for both Mayfair’s now burgeoning art world and the capital’s cultured visitors. Today, Craig-Martin is very much part of the art intelligentsia, championed by arguably the world’s most influential commercial gallery, Gagosian, and enjoying a far-reaching career of global exhibitions and teaching. But he retains something of a unique status – a veteran who still feels they might have something to prove. “I do think of myself as a maverick, and I don’t think I fit easily into any category,” he says. “And if you can’t be put in a category, you tend to not be put in at all.”

I’m trying to engage the audience in an appreciation and understanding of ordinary life.

Michael Craig-Martin

Craig-Martin makes work of inescapable modernity, but it is the early Renaissance that, for him, exemplifies art’s power. “At that time the average person never saw an image unless they had a coin: there were no pictures, prints or magazines,” he says. Churches were the awe-inspiring exception, filled with decorative frescos, sculptures and ornaments. “People went in and they were overwhelmed by what they saw. They recognised the stories and narratives; these super sophisticated works of art were made for – and understood by – ordinary people.” Now, of course, while our image environment is different, artists still have influence over our visual culture and the values it conveys. Craig-Martin sees his RA show as a chance to stimulate rather

than preach, and the audience as his partner. “I don’t have an agenda,” he declares. “I’m an observer and a recorder.”

Collaboration with the audience has defined Craig-Martin’s practice since the beginning. For his first London solo show in 1969, he presented visitors at the Rowan Gallery with sets of boxes that did not close or with their lids reversed (Box that Never Closes, 1967). “There was an action that was implied or asked for,” he says of the hinges or handles to be manoeuvred. This invitational mode of conceptualism found its most piercing form with An Oak Tree (1973) four years later, in which Craig-Martin presented a glass of water on a shelf accompanied by a written Q&A. “What I’ve done is change a glass of water into a full-grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water,” he explained in the text. Here the viewer is participant as both believer and sceptic. Craig-Martin smiles as he recalls a modestly sized audience, mostly other young artists, gathering on the opposite side of the gallery with their backs to An Oak Tree’s shelf, as interested in having a glass of wine as considering the work itself.

His methods of representation have evolved, but Craig-Martin’s emphasis on our shared experience of objects has remained the same. Drawings and paintings have taken the place of conceptual installations and his visual inventory has been updated to reflect how technological advancement has altered day-to-day life. “When I first started to draw, my sense of something ordinary was something very inexpensive that anybody could have,” he explains. Now people are just as likely to be carrying an iPhone as they are a pen – a drastic change in sophistication and value. Visitors to the RA will use credit cards to purchase tickets to the show. Many will take photographs of Craig-Martin’s work on iPhones. In unison they will recognise these objects in his works, as will the children who wander the galleries, he points out excitedly. “I’m trying to engage the audience in an appreciation and understanding of ordinary life,” Craig-Martin explains. Audience means everyone. Ordinary means everything. Depicting an iPhone (Untitled (iPhoneX), 2019) or a Coke can is not about endorsing commodification or even skewering modern technology, but about recognising that brands and objects now occupy as significant a space in our shared consciousness as religion or language. “It’s not to do with consumerism or possession,” Craig-Martin explains. “It’s to do with identification.”

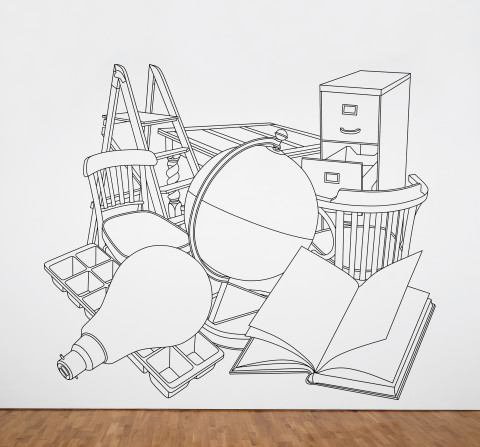

To understand Craig-Martin’s work today, you have to understand his approach to colour. And, perhaps most importantly, the fact that it was only in the 1990s that he began to employ the bold tones that now define his paintings. In the first 30 years of his career, Craig-Martin had developed a precise conceptual, sculptural and drawing practice rooted in both the geometric exactitude of 1960s Minimalism and the radical ontology of Marcel Duchamp. Works from that period in the RA show include On the Shelf (different amounts of water in 15 milk bottles on a slanted shelf forming a single horizon line), On the Table (four metal buckets suspended on a table top by ropes through ceiling pulleys) and Four Complete Clipboard Sets… Extended to Five Incomplete Sets (1971), comprising wall-mounted clipboards with erasers and pencils dangling beneath. All demonstrate Craig-Martin’s experimental but also economical impulses. Countless drawings on paper carefully map these early works. The late-1980s wall sculptures using Venetian blinds were made in black or dark red (Untitled (Red), 1988). Their colour was more restrained, less intriguing than the sections of white gallery wall they revealed, where, in another context, windows and the outside world would be. Craig-Martin’s retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1989 featured all of these and was fronted by Reading (with Globe) (1980), a tape wall-drawing of objects including a metal filing cabinet, ice tray and ladder. In influence and execution, he was at that point “an artist of the Seventies,” he explains.

Box That Never Closes, 1967

Untitled (Red), 1988

Reading with Globe, 1980

That all changed in 1993, when Craig-Martin decided to employ what he terms ‘big colour’ – painting a room, wall or surface in a single block shade. The Mexican modernist architect Luis Barragán, renowned for his use of a single colour over a large surface, was a key influence. For a site-specific installation at Galerie Papillon in Paris, Craig-Martin selected simple Dulux housepaints to colour each of the rooms a different intense hue, for example red, yellow, purple and blue. The reaction of the audience was a revelation. “People came into the gallery and smiled, responding viscerally and visibly,” Craig-Martin remembers fondly. Up to that point, his work had been described as ‘interesting’, he laughs, one of the art world’s more tepid descriptors. “When I introduced the colour, I had an emotive response, and that struck me.”

Craig-Martin had studied the colour theory developed by the Bauhaus veteran Josef Albers at Yale, but only then in Paris did he see how to use what he had learned at the art school – a bottom-up epiphany in his fifties that artists normally have in their twenties or thirties. It led to a painting practice which Craig-Martin now describes as his “centre of gravity.” The objects of everyday life are now transposed in acrylic onto aluminium or canvas, animated by a distinctive and non-mimetic colour palette. A cassette, a pencil sharpener, a chair, a globe and a bucket were his standalone subjects in the early 2000s. More recently he has featured a takeaway cup, laptop and watch. Works such as Eye of the Storm (2002) see multiple objects clash and intersect, a departure from Minimalist principles. “My early work does not appear to have a connection to the paintings,” Craig-Martin says. But there is more continuity than people realise. “Frankly, I see my work now as no less conceptual than my early work. But then people don’t think painting is conceptual.”

What makes these works so distinct? Clearly, they evoke the languages of advertising and product design, reflecting our era’s information abundance. But while the objects represented might appear generic, viewers bring subjective identification to their experience. Seeing a painted representation of an iPhone brings to mind the iPhone in one’s own pocket – a highly customised, personalised device filled with private information. “It’s the most extraordinary object to me because it’s the

blandest object you can draw,” Craig-Martin remarks. “But it incorporates a camera, a computer, a diary: thousands of functions which used to have individual objects, all of which had physical individuality, and all of which have disappeared into this one bland thing.”

It is the colour in his paintings that provides context and therefore “emotion and specificity” for the audience, he believes. “The term art is a generalisation. Works of art are always particular. And the more particular a work of art, the better it is.” Rembrandt could denote a velvet jacket, human flesh and a frilly collar within millimetres of each other, just through different shades of paint, he says. While he shares little with the Dutch master in terms of brushwork, the history of painting helps to explain his approach. A picture of a jacket is not the same as a jacket. But “it’s an equivalence” to which the viewer brings their own knowledge and experience. “The image itself could be a symbol, it could be just a picture, it could have a semiotic function. At root, there is the image.” The same logic applies to Craig-Martin’s portraits of people, including George Michael and the Duke of Wellington, as it does for his technicolour versions of Velázquez’s Las Meninas and Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (Reconstructing Seurat (Purple), 2004). An art historian would interpret these differently to a child, yet their existence as images – as information, irrespective of their readability – is universal.

Some things, though, cannot be depicted. Art, Death, Painting and Sex are rendered by the artist as word paintings, a comment on the limits of the image and a wry nod to effability (Untitled (Death), 2008). “I can’t draw art. I can’t draw death. I can’t draw abstractions because there’s no object,” Craig-Martin says. “And so the only words I’ve ever used in the work are abstractions.” His art is about exploring the nature of representation, and questioning the material and perceptive mechanics of the image. The works of American artists Sol LeWitt and Ed Ruscha Hon RA come to mind, which rely on both language and colour experimentation in painting. “The greatest miracle of picture-making is the fact that you can make a picture of something at all – and that we can read it. When we make a picture, we experience the thing that isn’t there.”

Eye of the Storm, 2003

Reconstructing Seurat (purple), 2004

Untitled (four laptops blue), 2024

Untitled (death), 2008

Craig-Martin’s interests haven’t always been in vogue, and a degree of patience has been involved in sustaining his long career. “The art world does work by decades, largely – whatever is going on in one decade is usually rejected by the following one,” he says. “In the 80s came the New Spirit in Painting [a resurgence of expressionist art]; that wasn’t really me and I found it difficult to know how to keep my feet. In the 90s I was very comfortable.” Craig-Martin was teaching at Goldsmiths at the time, mentoring future YBAs, including Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst, as well as Julian Opie, whose style most clearly echoes that of his mentor.

Art is a ‘calling’ rather than a job, Craig-Martin claims, but he doesn’t sentimentalise the sacrifices involved in forging a creative path. He is far more awed by dancers – the destruction of the body in the name of art – and throughout our conversation gratitude emanates rather than a sense of inevitability around his success. For six decades London has been his inspiration and resource. Now it is his plinth. “I’ve had a steady career, but never a big moment,” he concludes. “The big moment is this.”

Ravi Ghosh is a critic and Deputy Editor of the British Journal of Photography.

Michael Craig-Martin is at the Royal Academy of Arts from 21 September – 10 December 2024.

Enjoyed this article? Join the club

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

A love letter to the gallery gift shop

18 November 2024

Painting the town: Florence in 1504

15 November 2024

Moving a masterpiece

7 November 2024